The recent terrorist attacks in Lebanon, Tunisia, Turkey and France are some of the many attacks connected to ISIL and the ongoing civil war and humanitarian crisis in Syria, which resulted in millions of displaced people and refugees fleeing to protect their families. Unfortunately, 4.5 years have passed by and a solution on how to decrease violations of human rights and enforce security and protect civilians has yet not been fully identified. This article is based on my research and the field work conducted in Iraq during the summer of 2015.

“Once upon a time in the city that never sleeps”

In January 2015, under the academic guidelines of the Center for Global Affairs at New York University, and as part of the course called Workshop in Applied Peacebuilding taught by Clinical Professor Thomas Hill, I was assigned to join the World Education Foundation, a non-governmental organization working on a humanitarian project in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The scope of the project was to promote peace through education by creating an inclusive education framework for Syrian refugee youth between the ages of 15-25, Iraqi Internally Displaced Youth (IDPs), and the local communities of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

The CEO and Executive Director of the World Education (WE) Foundation, Mr. Marques Anderson, and my NYU graduate colleagues, Karin Attia and Janell Johnson, were the main members of our team in Iraq. Our field researchers were students from the Universities of Duhok and Kurdistan-Hewler, and our main funding partners were the UNDP, the UNHCR, and OpenIdeo, an open innovation platform solving, as quoted, “big challenges for social good”.

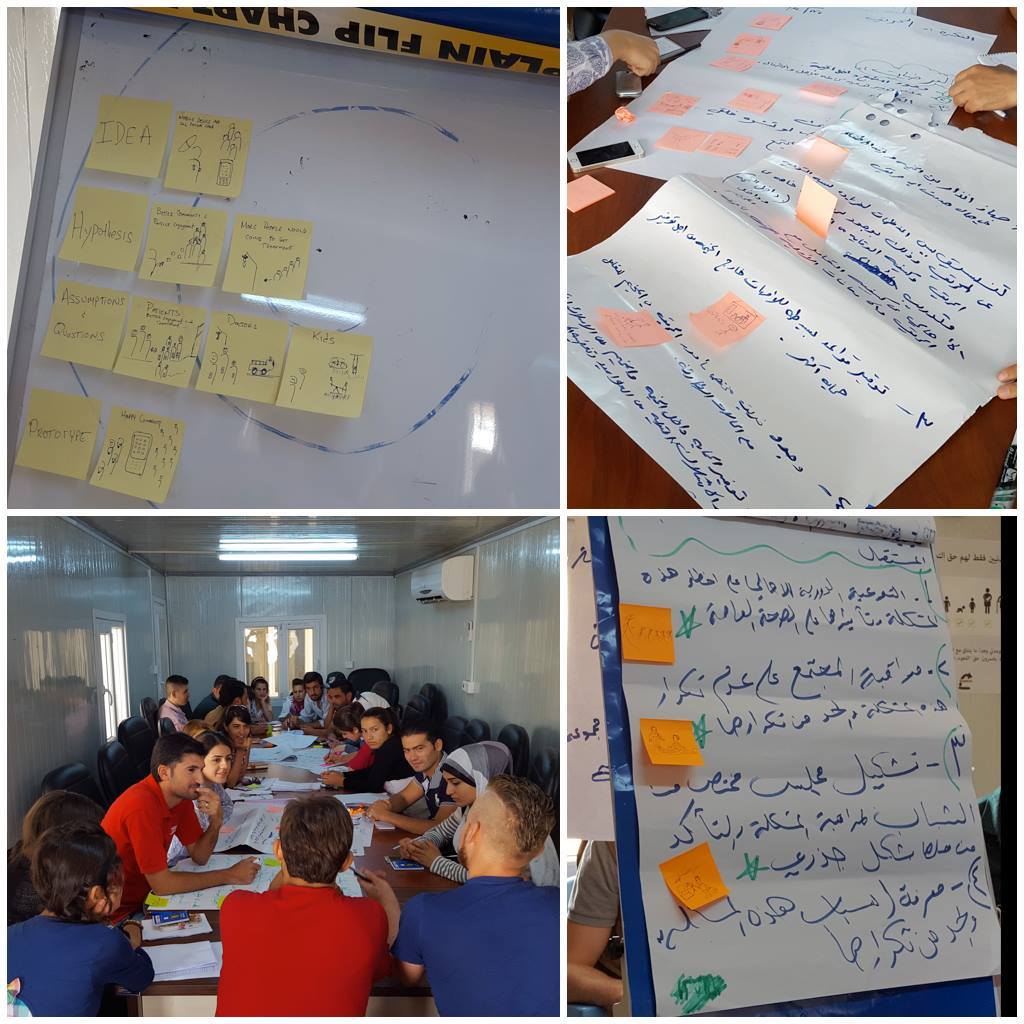

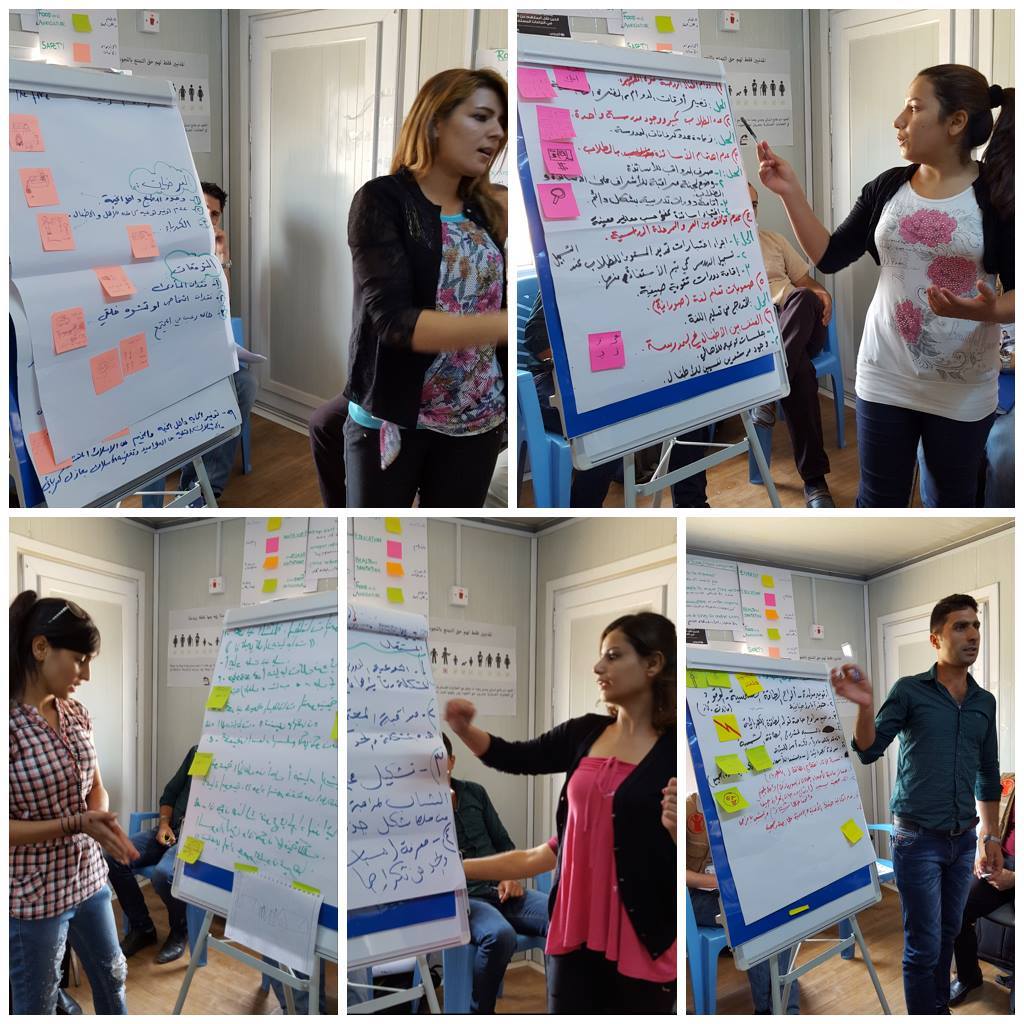

Our project, called WE: SOLVE Labs (Solution-Vortex-Environment), aimed to develop long-term solutions within the labor markets of the cities of Duhok, Erbil and Sulaymaniyah. The WE: SOLVE Labs focused on male and female youth, both Syrians and Iraqi Kurds. Taking into consideration the cluster areas of education, agriculture, energy, health, security and nutrition, we created a framework of trainings, workshops and social engagement with a duration of 13 weeks to be launched in the third quarter of 2016. These are aimed at refugee and IDP youth through identifying the needs of their own community, and engaging with the local communities to promote social cohesion, collaboration and peace between all actors involved. The key component of the WE: SOLVE Labs is teaching refugees and IDPs the skills they need to help them become more creative and labor-oriented while continuing their studies, so that they can then teach these skills to their own communities by taking initiative and promoting change.

“The Beginning of a Journey”

Throughout the semester, along with Karin, Janell and Marques we were working on the framework in order to have a better perspective and an overall estimate of the budget and the skills required, while getting ready for an unforgettable experience. Since this was my first ever field work experience, it was natural for me to have mixed feelings. On the one hand I was concerned how it would feel to apply all the theories I had been reading in books and academic papers for the past couple of years in New York directly in the field, and being part of an idea that would bring change and help thousands of people. On the other hand, it was also personal; I wondered whether or not I would be able to do field work, despite the academic knowledge and training, and whether or not I would be able to handle the unexpected nature of field work. In June 2015 we arrived in Iraq at our first stop in the city of Erbil. We were fascinated by the beauty of the city and the warm welcome from the Kurdish people. Before arranging our first meeting at the UN Compound, we had the opportunity to walk through the streets and visit the Bazaar with its various spices, Iraqi tea and delicious appetizers. We also visited the Erbil Citadel, the historical city center which has also been added to the UNESCO Heritage List.

“The meetings at the UN Compound and the NGO Regional Offices”

Our first meeting at the UN Compound in Erbil was with Mrs. Nelly Opiyo, the World Food Program’s (WFP) Senior Program Officer. We had the opportunity to discuss data concerning the influx of Syrian refugees and Iraqi IDPs as well as a potential collaboration for the WE: SOLVE Labs. Mrs. Opiyo, along with her team, informed us about some of the procedures they follow such as providing powdered milk rather than fresh milk. Powdered milk lasts longer and is easier to prepare, and there is limited storage in the camps due to lack of electricity and facilities. She also talked about land access in the refugee camps where thousands of families live without proper food and water access. Despite general nutrition monitoring by WFP and contributions from the UNHCR and UNICEF, Mrs. Opiyo added that they focus on children and women and that they also provide vouchers for refugees to buy food at the camp store when needed. Unfortunately, as we found out later on in our journey in Iraq, products at the camp stores cost double the normal price and refugees cannot afford them. In August 2015, the WFP initiated the “Process of Refugee Targeting”, which is responsible for providing additional evidence of Syrian refugees in the region, finding people at the household level living in endangered areas, and enhancing understanding of coping strategies around food consumption. Our conversation with the WFP Program Officer then turned from refugee nutrition to IDPs’ nutrition, and we had the opportunity to discuss the factors which deny IDPs proper nutrition such as their status and the lack of mechanisms and jurisdiction of authority associated with that status. At the UN Compound we also had a meeting with Mr. Paul Schlunke, the Senior Emergency Response Coordinator at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). We discussed extensively how the FAO provides water to the camps (three times a week), how they promote agricultural products and initiatives to the families living in them, and how the WE:SOLVE Labs could contribute to the processes of the FAO in the long term.

Our field work in Erbil also included meetings with the Ministry of Education of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and more specifically with the Director of International Relations. We discussed the differences between providing education to Iraqi IDPs and Syrian refugees. Iraqi IDP youth, due to their nationality, are able to attend schools, but it is not the same for Syrian refugee youth. This unfortunately happens for three main reasons: a) the language barrier; courses are being taught in Kurdish, and Arabic-speaking students are not able to comprehend the material, b) the increase of Syrian refugees and the limited number of teachers speaking Arabic, and c) the uncertainty of professional endorsement and successful job-seeking with the certificate that is given to Syrian students following completion of their studies, in case they return to Syria.

For the purpose of understanding the educational advancement of Syrian refugees, we arranged a meeting with the Education Manager of Save the Children, Mr. Mohammad Jamal, and the Project Manager, Mrs. Marco Alfieri. Save the Children, along with UNICEF, are the two main non-state actors actively contributing to the promotion of education among young boys and girls. The Save the Children volunteers and staff facilitate trainings for survival, protection, participation and development in refugee and IDP camps, urban areas and three urban centers. In terms of child protection, they have initiated the Child Residence Program for children under the age of 14 years old and the Youth Residence Program for ages 16-20 years old. We also discussed other issues such as child labor and early marriages in the region, how IDPs’ education still persists as a problem as there are no adequate facilities and IDPs prefer to work rather than go to school, and toilet accessibility in the camps. We also talked about the disadvantage of not speaking the Kurdish language or the local Arabic language, which is different from the one spoken in Syria. This creates an additional barrier to the engagement of refugees in the local communities.

“The Visit to the Refugee Camps of Domiz and Qushtapa”

And the moment had come: only 10 days after our arrival in Iraq, after meetings with universities and NGOs (such as the Norwegian Refugee Council, the Danish Refugee Council, ACTED, REACH and the Civil Development Organization), we were ready to visit the refugee camps in Erbil and Duhok. Special thanks to Mr. Alfieri from Save the Children, Mr. Alex Munoz, an NYU – University of Duhok consultant working in the field since 2012, and Professors Dr. Wrya Muhammad Ali and Saladdin Ahmed who introduced us to our local mentors: graduate students Roj, Jiyan, Matty and Juma. Due to time constraints we decided to conduct our first workshop in the Domiz Camp in the city of Duhok, and the second training at the Qushtapa refugee camp once we would return to Erbil.

“Theory of Change of WE: SOLVE Labs”

Our main purpose with the trainings and workshops in the refugee camps was not to gather refugees in a room and instruct them through PowerPoint slides, but to teach them the skills required to conduct needs assessments by identifying triggers, factors and problems within refugee camp communities, and then come up with practical solutions that could be useful for their own communities. Our project was designed to change the narrative of what it is to be a refugee; instead of “waiting”, we encourage them to take initiative and build their own future. Eventually, they would teach other members of their camp community. The active involvement of the local mentors helped with the skill training and the exploration of new market and technological aspects, essentially building peace and social cohesion through education. The initial number of refugee participants was 20 in both workshops, including our local mentors.

“The Inner Voice: It is Not about YOU”

The experience in the refugee camps was transformative in every possible way. We had the opportunity to meet and speak with refugees, and for a couple of days to be exposed to their daily life. I certainly consider these people as heroes. They have been through war, murder attempts, and attacks from combatants and extremist groups in the region. Thousands of civilians lost their lives due to bombs or direct attacks. Others have managed to escape and seek asylum in neighboring countries or travelled thousands of miles to live for an uncertain period of time in a refugee camp, a tent, or a “house” made of thin metal layers, where safety and security, nutrition, water accessibility, heat, medical supplies, education and electricity are daily and constant concerns for them as well as their families.

It is ironic how we have our laptops, our phone plans, our warm food and water, a cozy bed, and we complain and want more, while these people have lost almost everything and yet, they have not lost their “hope for a change”. Talking to them and being invited into their homes, I felt the generosity of the Syrian people, their warm hospitality and their desire to live. I felt honored to be invited into their tent and to be offered a warm and aromatic cup of tea, while due to Ramadan they would respectfully abstain from joining me in its pleasure. They introduced us to their family, including a five-month baby called Nadine, a beautiful baby girl. They would recount all the struggles they have been through. Nadine was born in the camp. Their smile reflects the emotional strength that makes them keep hoping for a better future for their children, one that includes learning English and going to school, being healthy and happy, and living the lives their parents had envisioned for them. However, the people in the refugee camps of Domiz and Qushtapa are also undeniably sad as they were forced to leave their country; they may have lost members of their family and communities. They are in pain, a pain displayed in their eyes and tears when remembering these special moments.

As Oscar Wilde once said, “the pure and simple truth is rarely pure and never simple”. And reflecting on refugees’ experiences is a responsibility of significant importance. I remember when we were collecting data with our local mentors and the refugee participants and they were interviewing their own community, I was proud to see that the majority of the 20 participants we had were girls and they were very enthusiastic about actively participating. One time, a very young girl, maybe less than five years old, approached us because she thought we were doctors. On her shoulder she was holding her baby sibling and in her other hand some medical documents. Her mother was watching us from a short distance of 5-10 feet from her small tent, and to my deep sadness and shock, I noticed she had only one leg and a pair of crutches. I was speechless. It was the first time in my field work in Iraq up to that point that I did not know how to react or what to think. The young girl looked into my eyes and she showed me once again the medical documents and her baby sibling. From the few Arabic words. I had managed to learn by then, I understood that she needed a doctor for the baby. I asked the local mentors to tell the girls we were not doctors but consultants working on an educational project for the camp. I know, I could have thought of anything else but at that point, I had a blank space of thoughts in my mind. And then, the young girl with tears in her eyes looked at me one last time; she smiled, and she said “okay”, and then she left back to her mother. And that was it. It was the kind of decisive moment that helps you decide whether you are able – and mainly if you are willing – to do field work and be engaged in peacebuilding; if you are capable to handle all the emotions and do the best you can, or just quit and go back home. No matter how hard field work can be, especially in conflict zones, you must always remember that “it is not about you” but about the people you are there to help. And in that moment, all the doubts I had prior to my trip evaporated like drops of water on a hot day. I was there to help in any way I could – because that girl deserves a better future. Even if we cannot achieve global peace, we can at least try to create a better environment where supporting basic human needs do not have to be considered as humanitarian assistance. We can promote education for the refugee and IDP youth so they can take the lead in the work that humanitarian workers have been doing all these years in Syria, Iraq and other volatile environments.

For further information on the Domiz Refugee Camp and our project, please visit the OpenIdeo link where we submitted our report for evaluation and received feedback that contributed positively to our second workshop in Qushtapa as well as the future workshops and trainings due to take place within the following months. Once again I would like to say how honored, blessed and fortunate I am to have participated in this project with the WE: SOLVE Labs, which will help thousands of Syrian refugee and Iraqi IDP youth as well as the local communities of the Kurdish Region of Iraq. The trip to Iraq, the interaction with refugees and the field work experience in general made me feel more human. It taught me how to listen more, how to understand and be able to decode cultural components, and to better understand why studying peacebuilding for me was the next step in the direction of peace, co-existence and change for a better future for everyone. It made me appreciate how the humanitarian crisis in the Middle East and subsequently in the Mediterranean became part of my graduate thesis at NYU, due to be completed in May 2016.

I would like to thank my WE: Team Karin, Janell and Marques for their contribution throughout our field work in Iraq as well as my professor, Tom Hill, for introducing me to the “world” of peacebuilding and his support throughout my academic years at NYU.

Yannis Bacalis is a graduate of the MSc In Global Affairs of New York University with specialization in Peacebuilding. He is a peacebuilding practitioner as well as a monitoring and evaluation specialist. He is an accredited mediator from the New York Institute of Peace and a long-term consultant for the Hellenic Association of Political Scientists (HAPSc) as the Main Representative at the United Nations in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) under the NGO Consultative Status. He completed his Bachelor studies in International and European Studies with specialization in Political Studies and Diplomacy at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki Greece and is fluent in English, Greek, Spanish and French. His main areas of interest involve refugees and vulnerable populations, women’s rights, development, mediation, conflict resolution, peacebuilding and education.